|

TECnology Hall of Fame 2007

Induction Ceremony: October

5, 2007

AES Convention, Javits Center, New York City

The TEC Foundation for Excellence

in Audio established the TECnology Hall of Fame

in 2004 to honor and recognize audio products

and innovations that have made a significant

contribution to the advancement of audio technology.

Inductees to the TECnology Hall of Fame are

chosen by a panel of more than 50 recognized

audio experts, including authors, educators,

engineers, facility owners and other professionals.

Products or innovations must be at least 10

years old to be considered for induction.

1919 Leon Theremin—The

Theremin

1925 Chester Rice & Edward Kellogg, General

Electric Co.—Modern Dynamic

Loudspeaker

1940 Dr. Walter Weber—AC

Tape Bias

1956 Neumann—Neumann

Stereo Disk Lathe

1957 Stefan Kudelski—Nagra

III Tape Recorder

1958 Cannon—XLR Connector

1959 Rein Narma—Fairchild

670 Compressor Limiter

1967 Crown International—DC

300 Power Amplifier

1970 Rupert Neve—Neve 1073

Console Module

1971 AKG—C-414 Condenser

Microphone

1972 MCI—JH-400 Series Inline

Console

1975 Eventide—H910 Harmonizer

1976 EMT—250 Digital Reverb

1978 3M—Digital Audio Mastering

System

1981 Sony—PCM-F1 Digital

Recording Processor

AUDIO

INNOVATIONS THAT CHANGED PRO AUDIO

By George Petersen

Edison's first cylinder recorder

was born 130 years ago, and while other technologies—from

automobiles to aerospace—emerged in that

era, audio is what counts for us true devotees.

Unfortunately, the history of pro audio is woefully

neglected, with sources scarce, if not impossible

to find.

An offshoot of the TEC Awards,

the TECnology Hall of Fame began in 2004 to spotlight

significant innovations in pro audio history.

Selecting a few inductees

from a more than a hundred years of heritage is

not easy. A committee of more than 50 industry

leaders, engineers, producers, educators and journalists

volunteered to help pick audio innovations—the

only “rule” being that any selection

must be at least 10 years old. Bear in mind that

the TECnology Hall of Fame is a continuing project

and more honorees will be added in the future.

Listed chronologically, here are the 15 entries

for 2007:

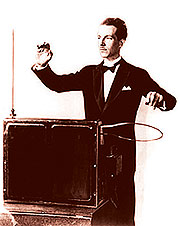

LEON

THEREMIN

THEREMIN (1919)

Who

would believe an innovative electronic musical

instrument developed in 1919 could maintain its

massive cult status and popularity after nearly

90 years? However, the Theremin is no ordinary

instrument. Who

would believe an innovative electronic musical

instrument developed in 1919 could maintain its

massive cult status and popularity after nearly

90 years? However, the Theremin is no ordinary

instrument.

Created by Russian physicist

Lev Sergeivich Termen (also known as Leon Theremin),

the Theremin is described in its U.S. patent (#

1,661,058) as a “novel method of and means

for producing sounds in musical tones or notes

in variable pitch, volume and timbre.” The

key word here is “novel,” as the system

consists of two oscillator circuits where amplitude

and frequency are controlled by the proximity

of the user’s hands to the Theremin’s

two antennas, with no need to actually touch the

instrument.

Over the years, there have

been numerous serious Thereminists, yet the instrument

is best known for creating outerworldly effects

and music for horror and science fiction films

ranging from the classic The Day the Earth

Stood Still to countless budget releases.

A common myth is that a Theremin was used on the

Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations."

The instrument was actually a Tannerin (Electro-Theremin)

played by trombonist Paul Tanner, which uses a

similar technology, but substitutes a hardware

slide controller for the antenna.

One well-known Theremin fan

was the late synthesis pioneer Bob Moog, who built

the units for decades and sold completed systems

and kits through Moog Music (www.moogmusic.com).

Moog also published a DIY Theremin project in

the Feb., 1996 issue of Electronic

Musician magazine.

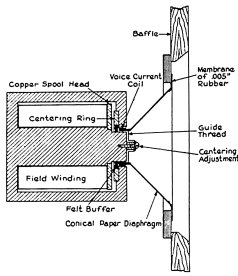

CHESTER RICE & EDWARD

KELLOGG, GENERAL ELECTRIC CO.

MODERN DYNAMIC LOUDSPEAKER (1925)

Timing

is everything and the development of the modern

dynamic loudspeaker by two General Electric engineers—Chester

W. Rice and Edward W. Kellogg—was right

on time. In a landmark article, “Notes on

the Development of a New Type of Hornless Loudspeakers,”

published in the Sept. 1925 edition of AIEE Transactions,

these two General Electric engineers describe

what we know consider the roots of modern loudspeaker

technology. Timing

is everything and the development of the modern

dynamic loudspeaker by two General Electric engineers—Chester

W. Rice and Edward W. Kellogg—was right

on time. In a landmark article, “Notes on

the Development of a New Type of Hornless Loudspeakers,”

published in the Sept. 1925 edition of AIEE Transactions,

these two General Electric engineers describe

what we know consider the roots of modern loudspeaker

technology.

After testing numerous materials

and approaches, Rice and Kellogg suggest a lightweight

(paper) conical diaphragm attached to a coil of

wire that’s energized by a large magnet

structure. In this proposal, the latter was an

electromagnet, as an affordable alternative to

the great expense of large permanent magnets in

those days. Beyond simply describing a new type

of transducer, the pair lay out many of the basic

tenets of loudspeaker design, such as detailing

the importance of the baffle in preventing the

“circulation” of the sound from the

speaker’s forward and backward motion. Rice

and Kellogg also discuss the need for more powerful

amplifiers to provide adequate headroom required

for quality reproduction, noting that before the

“full benefit of a high grade loud speaker

may be realized, it is important that the amplifier

which goes with it should have sufficient capacity

to give a natural volume or intensity."

The Rice/Kellogg electro-dynamic

speaker design was licensed to RCA, which incorporated

it into its successful Radiola line.

WALTER

WEBER

AC TAPE BIAS (1940)

Born

100 years ago, Dr. Walter Weber was a Siemens

engineer who was recruited by Dr. Hans Joachim

Von Braunmühl to work for Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft

(German Broadcasting) in 1932. While at RRG, von

Braunmühl assigned Weber to look into means

of improving the performance of AEG Magnetophon

tape recorders. Born

100 years ago, Dr. Walter Weber was a Siemens

engineer who was recruited by Dr. Hans Joachim

Von Braunmühl to work for Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft

(German Broadcasting) in 1932. While at RRG, von

Braunmühl assigned Weber to look into means

of improving the performance of AEG Magnetophon

tape recorders.

However, with the introduction

of BASF’s ferric-oxide tape in 1939, the

Magnetophon was approaching broadcast standards

and one of Weber’s interests was the application

of bias currents. Earlier research (such as by

Americans Wendell Carlson and Glenn Carpenter

in 1921) had shown that adding a high frequency

AC bias signal could raise the quality of magnetic

recording, but given the poor performance of wire

recorders, the improvement was minimal.

During experiments with a

DC biasing scheme in the spring of 1940, Weber

inadvertently applied a AC current to the recording

chain, leading to his rediscovery of the benefits

of AC biasing. The effect was dramatic, offering

a 10dB improvement in the Magnetophon’s

noise floor.

Weber filed a patent (German

#743,411) on July 28, 1940, and the AC biasing

technology was licensed to AEG, who incorporated

it into its Model K4 HF-Magnetophons that launched

a year later. And with a frequency response of

a then-astonishing 10kHz, tape recording was on

its way to eventually become the world production

standard.

Interestingly, one of Weber

and von Braunmühl's design projects had nothing

to do with tape. In 1935, they filed a patent

for the Braunmühl-Weber dual diaphragm capsule,

the first unidirectional condenser mic, which

eventually became the Neumann M7 capsule used

in the U47. In July of 1944, at age 37, Walter

Weber suffered a fatal heart attack, but his legacy

lives on.

NEUMANN

NEUMANN STEREO DISK LATHE (1956)

In

1953, Neumann engineers began developing the AM

32, a disk lathe with the ability of varying the

groove pitch, controlled by the amplitude of the

input signal, rather than a constant pitch. By

mounting a preview head on the source tape deck,

its signal could be fed to the lathe’s drive,

which made a small adjustment in the groove spacing

approximately one-half rotation before the cutterhead

received that same signal from the playback head. In

1953, Neumann engineers began developing the AM

32, a disk lathe with the ability of varying the

groove pitch, controlled by the amplitude of the

input signal, rather than a constant pitch. By

mounting a preview head on the source tape deck,

its signal could be fed to the lathe’s drive,

which made a small adjustment in the groove spacing

approximately one-half rotation before the cutterhead

received that same signal from the playback head.

Co-developed with Teldec (a

joint venture of English Decca and German Telefunken),

the Neumann ZS 90/45 stereo cutterhead arrived

in 1956 and combined vertical and lateral recording

in a V-shaped groove, each slope set at an angle

of 45 degrees. The ZS 90/45 was driven by the

VG1 (Verstärkergestell Eins) cutting electronics

with two 60-watt tube amps.

Besides controlling groove pitch, the system’s

SA 32 carriage could also use the difference between

the left and right signals to modulate the depth

of the cut and also adjusted the groove pitch

based on the depth of the cut, as deeper cuts

require wider grooves. This first electrodynamic

feedback stereo cutterhead system set the stage

for the world-standard SX 45, SX 68, SX 74 and

SX 84 cutterheads that followed.

STEFAN

KUDELSKI

NAGRA III TAPE RECORDER (1957)

Born

in 1929 in Warsaw, Stefan Kudelski was only 10

when his family fled Poland, to Hungary and France,

and finally settling in Switzerland in 1943. After

completing his college studies, he founded the

Kudelski company in 1951 and began creating the

Nagra (the name means "will record"

in Polish) portable recorder. Designed for high-quality

portable recording, the initial Nagra I and II

models were driven by a wind-up clockspring mechanism. Born

in 1929 in Warsaw, Stefan Kudelski was only 10

when his family fled Poland, to Hungary and France,

and finally settling in Switzerland in 1943. After

completing his college studies, he founded the

Kudelski company in 1951 and began creating the

Nagra (the name means "will record"

in Polish) portable recorder. Designed for high-quality

portable recording, the initial Nagra I and II

models were driven by a wind-up clockspring mechanism.

The breakthrough came

in 1957 with the Nagra III, a compact, 11-pound

mono 3.75/7.5/15 ips reel-to-reel deck. With 12

D cell batteries powering its DC servo-controlled

motor and Germanium transistor electronics, the

Nagra III's performance could rival much larger

studio machines. The deck's rugged aluminum chassis

and "Modulometer" peak-reading level

meter appealed to pros who needed a dependable,

near-indestructible location recorder.

With updates, such the addition

of Neopilot sync in 1963, the Nagra III soon became

the standard for location film recording and received

an Award of Merit from the Academy of Motion Picture

Arts and Sciences in 1965. After an 11-year span,

the Nagra III was eventually replaced with the

Nagra IV in 1968 and the Models 4.2 and stereo

IV-S in 1971.

CANNON

XLR CONNECTOR (1958)

Originally,

the XLR was intended for aircraft and instrumentation

applications—rather than audio—but

we’re glad it’s here. In use for balanced

pro audio for nearly 50 years, the three-pin versions

of Cannon’s XLR connector are so ubiquitous

in both analog and digital (AES/EBU) connections

that most people in our industry don’t even

remember those pre-XLR days. Once upon a time,

audio gear was fitted with whatever the manufacturer

deemed appropriate, with DIN and Tuchel connections

common in Europe and various Amphenol types in

the states. Originally,

the XLR was intended for aircraft and instrumentation

applications—rather than audio—but

we’re glad it’s here. In use for balanced

pro audio for nearly 50 years, the three-pin versions

of Cannon’s XLR connector are so ubiquitous

in both analog and digital (AES/EBU) connections

that most people in our industry don’t even

remember those pre-XLR days. Once upon a time,

audio gear was fitted with whatever the manufacturer

deemed appropriate, with DIN and Tuchel connections

common in Europe and various Amphenol types in

the states.

The move to Cannon’s

XLR design wasn’t exactly an overnight success,

taking at least 15 years, but it provided a universal

solution, where a mic cable could double as a

line cable and two cables could be connected to

make a single, longer cord. The XLR name stems

from being Cannon’s "X" Series,

with a latching/locking "L" feature

and having an elastomeric/rubber "R"

insulator.

Besides the common three-pin

XLR-3M (male) and XLR-3F (female ) connectors

in audio jacks and inline plugs, other XLR types

common to audio include 4-pin types for intercom

and 12-volt power connections, 5-pin stereo mics

and various multipin configurations for tube mics/surround

mics/etc. Today, XLR-style connectors are available

from many sources, including the original—now

ITT Cannon.

REIN

NARMA

FAIRCHILD 670 COMPRESSOR LIMITER (1959)

The

Fairchild 670 is often referred to as the "holy

grail" of outboard devices for its rarity,

value (currently about $30,000 on the used market)

and usefulness in a wide variety of studio situations.

And this hand-wired stereo unit is a beast, with

20 vacuum tubes (21 if you include the 5V4 rectifier)

and 14 transformers tucked within its 65-pound

chassis. The

Fairchild 670 is often referred to as the "holy

grail" of outboard devices for its rarity,

value (currently about $30,000 on the used market)

and usefulness in a wide variety of studio situations.

And this hand-wired stereo unit is a beast, with

20 vacuum tubes (21 if you include the 5V4 rectifier)

and 14 transformers tucked within its 65-pound

chassis.

The origins of the 670 (and

mono 660 version) are fairly humble, coming from

Estonian-born Rein Narma. In the post-war years,

this refugee from Soviet Russia worked for the

U.S. Army as a broadcast/recording tech during

the Nuremberg trials, later immigrated to the

New York and took a job at Gotham Recording. Narma

and several others founded Gotham Audio Developments,

to build recording gear. Les Paul hired him to

modify his first 8-track and later Narma built

consoles for Rudy Van Gelder, Olmsted Recording

and Les Paul, who also asked him to build a limiter.

After beginning the project, Sherman Fairchild

heard about it, licensed the design and hired

Narma as the company's chief engineer.

CROWN

INTERNATIONAL

DC 300 POWER AMPLIFIER (1967)

In

many ways, the 1967 introduction of the AB+B-class

DC 300 ushered in the era of the modern, high

power amplifier. Offering 340 watts/channel (at

4 ohms), this 4-rackspace, 40-pound beast came

in at less than the "magic" $1/watt

price point, based on its original $685 retail.

And with its rock-solid construction, and internal

thermal and V-I protection modes, the DC 300 was

the ideal solution for high-end consumers, high-SPL

studio monitors and live sound systems coming

into vogue with the summer of love. In

many ways, the 1967 introduction of the AB+B-class

DC 300 ushered in the era of the modern, high

power amplifier. Offering 340 watts/channel (at

4 ohms), this 4-rackspace, 40-pound beast came

in at less than the "magic" $1/watt

price point, based on its original $685 retail.

And with its rock-solid construction, and internal

thermal and V-I protection modes, the DC 300 was

the ideal solution for high-end consumers, high-SPL

studio monitors and live sound systems coming

into vogue with the summer of love.

Yet through it all, someone

at Crown has always maintained a sense of humor.

The original service manual for the DC 300 is

entitled "300 Watts and a Cloud of Smoke"

and its introduction includes advice such as "try

to avoid going to sleep while reading the rest

of this manual."

Years later, a DC 300 was

immortalized in a magazine ad that showed the

unit half-submerged in a muddy field, based on

a real story:

"In the early

evening of September 17, 1973, Jay Barth was at

the wheel of a 22-foot utility truck that was

loaded with sound equipment. Just north of Benton

Harbor, Mich., an oncoming car crossed the center

line; fortunately, Jay steered clear of the impending

collision. Unfortunately, a soft shoulder caused

the truck to roll two and one half times. Exit

several DC 300As through the metal roof of the

truck's cargo area. The airborne DC 300As finally

came to rest—scattered about in a muddy

field, where they remained partially submerged

for four and a half hours. Jay miraculously, escaped

injury; the amplifiers apparently had not. Unbelievably,

after a short time under a blow dryer, all the

amps worked perfectly and are still going strong.

The rest—and the truck—is history."

Even today, some 40 years

after their original introduction, many DC 300s

are still used in professional audio applications,

a testament to Crown reliability.

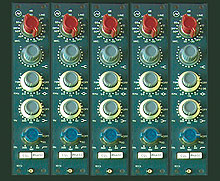

RUPERT

NEVE

NEVE 1073 CONSOLE MODULE (1970)

In

1970, Rupert Neve designed the first 1073 mic

preamp module for a new A88 console for Wessex

Studios. It became a legend, still widely regarded

as one of pro audio's best preamplifiers. The

Class-A design 1073 mic/line preamp has three

EQ bands (a fixed 12kHz HF band and switchable-frequency

LF/MF cut/boost bands) and a passive -18dB/octave

high pass filter with 50/80/120/160 Hz steps.

EQ bypass and "phase" (polarity) switches

are also standard. In

1970, Rupert Neve designed the first 1073 mic

preamp module for a new A88 console for Wessex

Studios. It became a legend, still widely regarded

as one of pro audio's best preamplifiers. The

Class-A design 1073 mic/line preamp has three

EQ bands (a fixed 12kHz HF band and switchable-frequency

LF/MF cut/boost bands) and a passive -18dB/octave

high pass filter with 50/80/120/160 Hz steps.

EQ bypass and "phase" (polarity) switches

are also standard.

Designed as 80-series console

modules and not originally intended for standalone

use, Neve's 1073s and 1084s were often removed

from older consoles and put into third-party racks

and housings. The circuit has been widely imitated

and cloned (in both hardware and software) and

the Neve company now offers recreations of the

1073 in rack and module form.

But according to Rupert Neve,

the secret to the original 1073's success was

transformers: "I've thought about this a

lot," Neve recalls, "and it had to be

in the input and output transformers and that

way in which the response rolls off. If you take

a very large rise time signal and throw it at

a stage that's not man enough to take it, you

get slew rate problems. There are few things that

sound more elusive or worse than slew rate problems—it

just doesn't sound right, with a soggy sound.

What we did with the transformers was to build

them out like filters to the maximum that we could

squeeze out in terms of high frequency response

and then make sure they rolled off smoothly—with

no peaking or things of that sort."

AKG AKG

C 414 CONDENSER MICROPHONE (1971)

The availability of reliable,

quality Field Effect Transistors in the 1960s

opened the door for replacing tube mics with compact,

solid state models. In 1970, AKG's Karl Peschel

took the CK 12 capsule from the C 12A Nuvistor

tube mic and paired it with FET electronics, resulting

in the C 412. A year later, adding a second bass

rolloff position and a fourth polar pattern created

the C 414 comb.

From 1974 onwards, engineer

Norbert Sobol supervised the C 414 design, adding

numerous improvements in audio performance and

features along the way. These included the C 414

EB (1976), C 414 EB-P 48 (1980), models C 414

B-ULS and –TL (1986), C 414 B-TL II (1993)

and the current C 414 B-XLS and –XL II.

With well over 100,000 sold,

the C 414 remains a popular choice whether in

earlier versions or the latest models—now

updated with LED displays and a fifth (wide cardioid)

pattern.

MCI

JH-400 SERIES INLINE CONSOLE (1972)

MCI

Electronics founder Grover C. “Jeep”

Harned was a pro audio innovator, from the first

24-track recorder—a modified Ampex 300 in

1968—to the tape Auto Locator (1972) and

commercializing the inline console. Credit for

the first inline-style console designs actually

goes to Dan Flickinger, who designed a number

of custom mixers that put tape monitoring within

the channel modules, but had track assignments

in a separate section. However, the popularity

of the modern inline console stems from Nashville

audio dealer Dave Harrison (later founder of Harrison

Consoles), who approached Harned with this new

approach to console design. MCI

Electronics founder Grover C. “Jeep”

Harned was a pro audio innovator, from the first

24-track recorder—a modified Ampex 300 in

1968—to the tape Auto Locator (1972) and

commercializing the inline console. Credit for

the first inline-style console designs actually

goes to Dan Flickinger, who designed a number

of custom mixers that put tape monitoring within

the channel modules, but had track assignments

in a separate section. However, the popularity

of the modern inline console stems from Nashville

audio dealer Dave Harrison (later founder of Harrison

Consoles), who approached Harned with this new

approach to console design.

Harned and MCI engineer Lutz

Meyer helped Harrison refine the JH-400. In a

day when most studio consoles were custom, the

JH-400s were revolutionary: They were standardized

"production" models with a choice of

user options and incorporated Harris 911 IC op-amps,

thus lowering costs and simplifying manufacturing.

The first JH-416 models offered 24 inputs/outputs

with quad panning/monitoring, 3-band EQ and P&G

faders. Options included a 32-input version, VCA

grouping and automation and switchable peak/VU

meters. The JH-400 (the "JH stood for Jeep

Harned) offered an affordable pro console to the

burgeoning studio industry and five years later,

a 1977 Billboard poll gave MCI the leading

share (14.3 percent) among studios. That same

year, MCI unveiled the updated JH-500 series,

which offered a four-band EQ, more sends/returns

and plasma VU displays.

Harned sold MCI to Sony in

1982 and retired. He will long be remembered as

a pioneer who made significant advancements to

the state of pro audio.

EVENTIDE

H910 HARMONIZER (1975)

When

you name a product after a Beatles tune (the model

number refers to the “One After 909”),

it better be good. However, when Eventide founder

Richard Factor assigned his young designer Anthony

Agnello (the company’s first “degreed”

engineer) to begin building a harmony processor

in 1974, they had no idea that they’d be

creating an audio classic of their own. The version

they demoed at the AES show later that year didn’t

resemble the final product at all, with a music

keyboard controller supported by a hand-wired

box, but the reaction was universally positive,

both among showgoers and Yes vocalist Jon Anderson,

who tested the first prototype. Soon after (and

with the keys controller offered as an option),

the Harmonizer H910 was born. When

you name a product after a Beatles tune (the model

number refers to the “One After 909”),

it better be good. However, when Eventide founder

Richard Factor assigned his young designer Anthony

Agnello (the company’s first “degreed”

engineer) to begin building a harmony processor

in 1974, they had no idea that they’d be

creating an audio classic of their own. The version

they demoed at the AES show later that year didn’t

resemble the final product at all, with a music

keyboard controller supported by a hand-wired

box, but the reaction was universally positive,

both among showgoers and Yes vocalist Jon Anderson,

who tested the first prototype. Soon after (and

with the keys controller offered as an option),

the Harmonizer H910 was born.

“With memory

for audio was just becoming possible, the H910

was the right box at the right time,” says

Agnello. Offering pitch shifting (±1 octave),

delay (up to 112.5 ms), feedback regeneration

and more from an easy-to-use $1,600 box, the H910

was a hit—an instant studio fave and still

a legacy tool years later. Users soon found all

sorts of applications, ranging from regenerative

arpeggios to bizarre sound design effects to lush

guitar or vocal fattening. The first customer—New

York City’s Channel 5—immediately

put an H910 to work, downward pitch shifting “I

Love Lucy” reruns that were sped up to squeeze

in more commercials. “The Harmonizer could

be used for good or evil,” warns Agnello,

“and the speeded-up sound of Lucy’s

occasional shrill shrieks was definitely evil.

Taming that was a good thing.”

Artists loved the Harmonizer’s

versatility. Frank Zappa put one in his guitar

rack. Producer Tony Visconti used it for the memorable

snare sounds on David Bowie’s Young Americans;

ditto for engineer Tony Platt on AC/DC's Back

in Black. Eddie Van Halen had a pair (set

to either 18-cents sharp and 18-cents flat with

a 12ms delay on one side or +12c/-15c/18ms) as

part of his trademark guitar sound. Tom Lord-Alge’s

setup for Steve Winwood’s soulful vocals

on “Back in the High Life” also employed

two slightly detuned H910s (one sharp/one flat)

with an 18ms spread. The twin Harmonizer effect

was so popular that Eventide recreated it as the

“Dual 910” program in the H3000 UltraHarmonizer

that followed it a dozen years later.

EMT

MODEL 250 DIGITAL REVERB (1976)

Considered

one of the pioneers of digital audio, Barry Blesser

helped launch Lexicon in 1971 and developed the

EMT 250, the first commercial digital reverb,

in 1976. EMT (Elektromesstechnik) was no stranger

to reverb, having created the classic Model 140

plate system back in 1957 and the gold foil Model

240 in 1970. As Blesser had designed a number

of EMT analog products in the early 1970s, the

collaboration of EMT and Massachusetts-based Dynatron

made sense. Considered

one of the pioneers of digital audio, Barry Blesser

helped launch Lexicon in 1971 and developed the

EMT 250, the first commercial digital reverb,

in 1976. EMT (Elektromesstechnik) was no stranger

to reverb, having created the classic Model 140

plate system back in 1957 and the gold foil Model

240 in 1970. As Blesser had designed a number

of EMT analog products in the early 1970s, the

collaboration of EMT and Massachusetts-based Dynatron

made sense.

Barry Blesser and Karl-Otto

Bäder designed the algorithms (U.S. patent

#4,181,820); Dynatron's Ralph Zaorski designed

the digital hardware; and EMT built the converters,

I/Os, power supply and the unique user interface,

with its large upright chassis and rocket ship-style

control levers for decay and delay. Its 400 ICs

and 16K of memory of this one-in/four out unit

required three fans and heat sinks covering the

entire cabinet exterior. "We put the power

supply on the outside and painted it red,"

Blesser recalls. "We took all the problems

and turned them into unique signature symbols."

The EMT 250 carried a $20,000

price on its debut and some 250 units were produced,

many of which are still in use today and valued

for their effects and reverb sounds. A later model,

the EMT 251, added an LCD readout, improved HF

response and more flexibility, but the algorithm

was not the same as the classic EMT 250.

© Peter Bermes (Bermes Design)

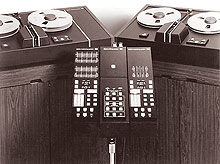

3M

DIGITAL AUDIO MASTERING SYSTEM (1978)

Best

known for its lines of tape media and professional

analog recorders, with its M series of multitrack

and 2-track machines, the Mincom division of 3M

spent several years developing a digital recording

system, including two years of joint research

with the BBC. The result was the 3M Digital Audio

Mastering System, which consisted of a 32-track

deck (16-bit, 50 kHz audio) running 1-inch tape

and a 4-track, 1/2-inch mastering recorder. Best

known for its lines of tape media and professional

analog recorders, with its M series of multitrack

and 2-track machines, the Mincom division of 3M

spent several years developing a digital recording

system, including two years of joint research

with the BBC. The result was the 3M Digital Audio

Mastering System, which consisted of a 32-track

deck (16-bit, 50 kHz audio) running 1-inch tape

and a 4-track, 1/2-inch mastering recorder.

Both decks operated at 45

ips, offering a 30-minute record time from a 7,200-foot,

12.5-inch reel or 45-minutes from a 14-inch, 9,600-foot

spool. Perhaps the most curious aspect of the

3M system was its conversion scheme. As no true

16-bit converters were available, it combined

separate 12-bit and 8-bit converters to create

16-bit performance.

Although the 3M system was

a year away from actual deliveries, engineer Tom

Jung (now of DMP Records) agreed to beta-test

the prototypes at Sound 80 in Minneapolis, using

them as a backup system during sessions being

cut direct-to-disk—lacquer disk, not hard

disk! The digital session tapes were judged superior

to the disk masters, and in December 1978, the

first commercial albums cut on the system were

released: Flim & The BB's, by jazz group Flim

& The BB's, and Aaron Copeland's Appalachian

Spring, by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. The

latter was nominated for three Grammy Awards,

winning for Best Chamber Music Performance.

Priced at $150,000 ($115,000

for the 32-track and $35,000 for the 4-track),

the first two-machine systems were installed in

early 1979 at Sound 80 and in Los Angeles at A&M

Studios, the Record Plant and Warner Bros.' Amigo

Studios. Among the notable early pop releases

cut on the 3M system included Ry Cooder’s

Bop Till You Drop (engineered by Lee Herschberg)

and Donald Fagen’s The Nightfly, engineered

by Roger Nichols.

SONY

PCM-F1 DIGITAL RECORDING PROCESSOR (1981)

Once

in a while, an audio product arrives that’s

a failure in the consumer realm (such as the DAT

format or Yamaha’s NS-10 speakers) but is

a hit with pro recordists. Sony’s PCM-F1

is one such example. Originally designed as a

means for consumers to make digital recordings

of CDs, FM broadcasts or home performances, the

PCM-F1 debuted in 1981. Once

in a while, an audio product arrives that’s

a failure in the consumer realm (such as the DAT

format or Yamaha’s NS-10 speakers) but is

a hit with pro recordists. Sony’s PCM-F1

is one such example. Originally designed as a

means for consumers to make digital recordings

of CDs, FM broadcasts or home performances, the

PCM-F1 debuted in 1981.

Essentially, the system combined

a recording processor that used the EIAJ’s

(Electronic Industries Association of Japan) 14-bit

PCM specification for digitizing audio and storing

it as a video signal—essentially a moving

monochrome barcode. The concept of a two-piece

system (connecting a PCM processor to any VCR—Beta,

VHS or U-matic—for recording) was unpopular

with consumers, but at $1,900, Sony's PCM-F1 was

a hit with studios. The Technics SV-P100 ($3,000)

went one step further: It was a 14-bit EIAJ processor

combined with a VHS transport. Years before DAT,

it was the first digital audio cassette recorder,

and Mobile Fidelity even released a few projects—such

as Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon—on

stereo PCM VHS tapes.

PCM processors from Aiwa,

Akai, Sansui, JVC and Technics rigidly stuck to

the 14-bit EIAJ standard; only Sony's PCM-F1 as

well as the later PCM-701/501/601 units and the

Nakamichi DMP-100—a black-finish F1 with

improved analog components—offered a choice

of (switchable) 14/16-bit performance. Apogee

Electronics once sold upgrades for replacing a

PCM-F1’s anti-aliasing filters with high-performance

Apogee versions.

Recording on EIAJ digital

processors had its ups and downs. Being video-based,

the system recorded at 44.056 kHz rather than

44.1kHz and digital editing was difficult—at

best—and only frame-accurate, requiring

a high-end assembly editing rig with multiple

synchronized decks. On the plus side, the processors

had no moving parts, so a worn-out transport simply

meant finding another VCR; and tape clones/backups

could easily be made using two VCRs. And as the

PCM-F1 had separate encode and decode circuitry,

four-track, sound-on-sound recordings were possible

using one processor and two VCRs (one designated

as play/the other as record). Alternatively, one

could make simultaneous 4-track recordings by

combining the PCM digital tracks with a video

deck’s “Hi-Fi” tracks. This

was great for live recordings where a board mix

or close-in mics went digital and room ambience

or mix position mics routed to the Hi-Fi tracks.

Paired with the optional

SL-F1 Betamax deck, the PCM-F1 was the first portable,

battery-operated digital recording system. A few

brave souls—myself included—even went

so far as to make multitrack recordings using

two (or more) synchronized PCM-F1s. But one thing

was certain: whether stereo or 4-track, the democratization

of digital had arrived.

Mix executive editor George

Petersen also runs a small record label (www.jenpet.com),

and still owns several Sony PCM-F1s, but hasn't

used them recently.

For more information, click

here.

|